Tanis, beloved SAFE horse, was laid to rest last week under a warm blue sky following a sudden and painful colic.

As is the case with colics, they can escalate quickly from seemingly mild into devastating rather quickly. We first noticed something was amiss around turnout time, when after finishing her grain mash breakfast, Tanis was down in her stall. Horses lying down when there is food around is uncommon, and often times a sign that something was wrong. And indeed, as we gathered our tools to take vitals, Tanis went up and down in her stall several times, rolling and clearly uncomfortable. We called the vet immediately, who told us to give banamine and keep her posted. We removed Tanis from her herd so we could keep an eye on her, spending the hour it took the banamine to kick in walking her around the roundpen and trying to keep her from going down to roll. Her respiration rate was very high (in the 40s), and her heart rate was elevated as well.

After an hour, while there was perhaps a mild improvement of her symptoms, she was still uncomfortable. Her vitals were still abnormal, and when we communicated all this with the vet, she made a plan to make it out as soon as she was able. Then it was about playing the waiting game. Tanis, for the most part, was standing still, and was her breathing not so heavy and her heart rate so high, it would have been easy to think she was feeling okay. But every few minutes, she would get a sudden urge to roll, trotting off and buckling her knees to go down. Per our vet’s wishes, we kept her upright during these times, but allowed her to walk out as long as she remained standing. She passed a normal sized pile of manure, but that did not seem to make any difference in the way she was feeling.

The vet arrived, and sedated Tanis for a rectal exam. Despite not being fond of needles, Tanis was a trooper for her IV sedation, even when it was clear she was feeling the ‘need to roll’ urge. Her first rectal revealed not a ton of motility, which made it difficult for our vet to feel very far in. She chose to ultrasound, which revealed a fair amount of gas, and a stomach that was distended past the point of being normal. At that point, we felt we were dealing with a gas colic, which was consistent with her painful symptoms, and the next steps would be to try and help her expel some of that gas through regular bouts of exercise. We made a plan to check back in, and would get Tanis moving as soon as she woke up from her sedation.

In the roundpen, we tried all manner of things to help Tanis pass gas. When plain trotting out wasn’t doing it, we introduced some things that normally would have really got her moving — waving empty grain bags around, tossing the rope over her back and having her change eyes on it, working her with the flag in areas that she still had trouble. But not only was she more subdued about all these things, she was also not expelling any of that gas. At the end of her rest periods, we took her heart rate, and found that it was even higher than before. After a bit more time (including a ride on the trailer, normally a sure fire way to get a horse’s guts moving), we checked back in with our vets.

They came out again. Another rectal revealed that same gas as before, and this time they were able to successfully intubate her, where they found she had some reflux. Things just weren’t moving through. They ultrasounded again, and found that on her right side, there was gas in places it shouldn’t be. Our vet felt that based on the imaging, something had ruptured in her small intestine — the cause was unclear, but the end result was the same, there was nothing that could be done. Her heart rate at this point was in the 80s, and despite being under heavy sedation, she was still hugely uncomfortable. But stoic Tanis did not allow much pain to seep through her surface. She was tremendously brave up until the end.

We walked her out into the grass. It was a warm, sunny fall day. We said goodbye under a tree shedding its leaves, and Tanis was laid peacefully to rest with a big mouthful of grass, surrounded by so many people who had loved her deeply.

We tell the story of a horse’s last day to inform everyone what happened, to offer transparency as to why we made the decision that we did (or, in this case, why that decision was made for us). But there is so much more to a horse’s story than how we lost them. It is also about how we found them, and how they came to find themselves.

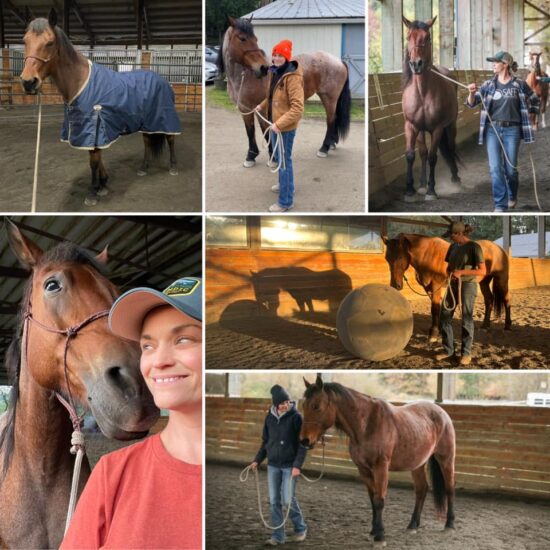

Tanis was born in 2003 on the Hog Creek HMA in Oregon. She arrived at SAFE in early 2022 with a rope someone had used to tag her still around her neck. She was unhandled, but with a kind eye and a curiosity towards people. Her first “person” here was Kaya M, who halter started her and taught her that people weren’t so bad (and that they could scratch her jowls in just the way she liked). From there, she continued her gentling journey alongside Meghan N, who spent countless hours showing her how to be more comfortable as a horse, but also what it meant to be loved by a human. Tanis was a participant in many Joel Conner clinics where she was both a student and a teacher to friends like Sara H and Candi K, among others. Tanis touched just as many people as touched her, if not more.

While Tanis was never adopted out, that does not by any stretch of the imagination mean she did not have a family. Each volunteer who filled her hay bag and picked out her stall and paddock was a part of her life, and her transformation from shy and untouched to brave and friendly.

When she was not interacting with people, Tanis was out with her group of mares, playing second-fiddle to Esme, and using her big beautiful body as a block for her friends to hide behind to avoid being caught. She was the first to welcome Wren into the herd, and was a phenomenal herdmate. She enjoyed sun naps alongside her pasture mates, gulping down sweet waters, and being first in line for grass turnout.

We will remember Tanis as a gorgeous, courageous mare, who rose from a scared and unhandled horse into the sweet, gentle giant she was destined to be.